Richtech Robotics $RR: How a Chinese Import Pipeline Masquerading as U.S. Robotics Monetized Perception Over Product

Richtech Robotics (NASDAQ: RR) The Illusion Loop: How a Chinese Import Pipeline Masquerading as U.S. Robotics Monetized Perception Over Product

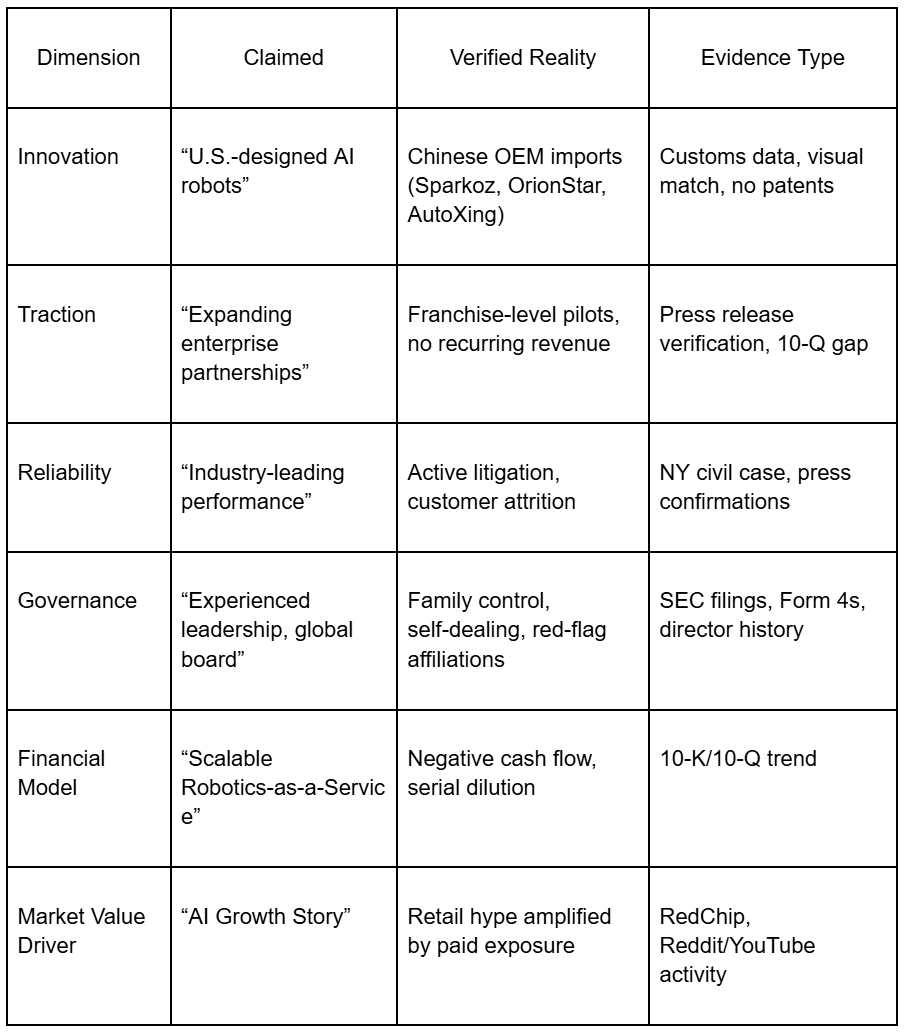

Richtech Robotics markets itself as a U.S. AI-robotics innovator. Public filings and third-party evidence tell a different story: an import-distribution chain routed through Shenzhen, wrapped in patriotic branding, and sustained by continuous publicity and equity issuance.

The company’s real engine isn’t technology or manufacturing—it’s narrative monetization, where attention becomes liquidity and liquidity sustains more attention.

Executive Summary — The Illusion Loop

Imported, not invented. Flagship robots mirror Chinese OEM hardware with no verifiable U.S. design IP or domestic production assets.

Pilots sold as contracts. “Enterprise” deals frequently prove to be one-off pilots or franchise placements.

The loop itself. PR spikes fuel dilution; dilution finances new PR in a self-reinforcing cycle.

Reliability problems limit scale. Mechanical failures, support burdens, and lawsuits hinder adoption.

Cash from stock, not sales. Revenue stagnates while losses widen and share count climbs.

Insiders win, holders dilute. Super-voting stock and low-cost insider awards transfer value upward.

Reality check. RR operates as a reseller of imported systems—a financial instrument masquerading as robotics innovation.

1. The Pitch vs. the Product: Where the Illusion Cracks

Richtech’s marketing emphasizes “U.S.-designed autonomous service robots built from the ground up.”

Public import data and product teardowns suggest otherwise.

A. Hardware Overlap and Supply-Chain Origin

Cleaner series: DUST-E S/MX units replicate Sparkoz TN-series designs—nearly identical chassis, sensors, and UI within millimeters of tolerance.

Service platforms: The ADAM bartender and coffee robots use motion modules and controller boards consistent with OrionStar’s commercial platform; technicians report plug-compatible parts.

Direct OEM availability: AutoXing Robotics and other Chinese manufacturers sell the same or near-identical units directly to U.S. buyers at lower prices.

Implication: When identical hardware is available from the original factories, Richtech’s claimed design advantage disappears. The firm functions as a marketing-driven reseller, not a proprietary manufacturer.

B. Disclosures vs. Evidence

Corporate materials reference “U.S. design and manufacturing,” yet:

Customs records list Richtech Technology (Shenzhen) as the exporter of record on multiple shipments.

No confirmed factory-scale facility exists in Nevada or Texas.

The USPTO database shows no granted utility patents tied to Richtech.

Capital spending disclosures emphasize equity registration, not production assets.

Result: The “American robotics” image exists mainly in filings and press copy. A quick search of industrial property records supports the absence of a domestic manufacturing footprint.

C. Economic Consequences

Comparable systems from OEMs cost 50–70 % less than Richtech’s pricing. Procurement teams can source equivalent robots through Sparkoz, OrionStar, or AutoXing, removing Richtech’s pricing leverage.

With margins compressed and no IP barrier, RR resembles a thin-spread importer dependent on storytelling to maintain valuation.

2. PR Alchemy — Pilots Dressed as Enterprise Wins

The company’s largest share-price surges correspond not to earnings beats but to press releases announcing “strategic partnerships.”

A. Pattern of Public Relations vs. Performance

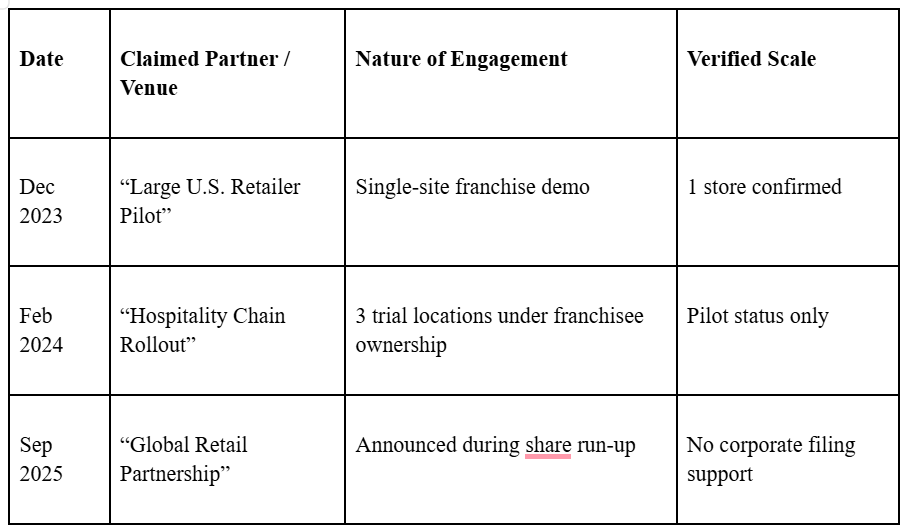

Timing correlation: Spikes in Dec 2023–Feb 2024 and Sep 2025 track precisely to partnership headlines; quarterly filings in those periods show flat revenue and deeper losses.

Scale inflation: Announcements reference “national retailers,” yet verification shows single-site or franchisee pilots.

· Lack of follow-through: No later filings confirm conversion of these pilots into recurring deals.

Inference: Headlines substitute for adoption data. Press becomes the growth engine when operations stall.

B. Structural Indicators of Promotional Behavior

Announcement volume: From IPO through mid-2025, Richtech issued more than 40 press releases—remarkably high relative to a sub-$20 million revenue base.

Recycled themes, few metrics: Each release repeats phrases like “expanding partnership” or “AI capability” without quantifiable contract values; no backlog or purchase commitments appear in filings.

Proximity to financing: Announcements frequently cluster within days of S-3, S-8, or resale registrations, implying a coordination between publicity cycles and capital-raising windows.

Cross-channel amplification: Exchange ceremonies, paid IR outlets, and social-media reposts extend visibility long after the initial event, creating the illusion of momentum.

Sparse conversion evidence: Subsequent quarters rarely show a material revenue impact from the touted partnerships.

Added context: These communications often coincide with investor conferences and trade-show calendars—maximizing perceived exposure even when the actual installations remain limited pilots.

C. Investor Interpretation

The pattern suggests a promotional information strategy rather than operational transparency.

Publicity builds perceived scale; filings later reveal stagnation. In this loop, attention becomes the company’s most monetizable asset.

3. Unit Reliability and Customer Churn — The Operational Weak Link

Commercial success depends on uptime and repeat orders. Evidence points to both being weak.

Litigation: Richtech’s Aug 2025 10-Q discloses a New York civil suit over ADAM robot performance (~$600k claim). The existence of the case confirms that field issues are real, not hypothetical.

Pilot attrition: Walmart One Kitchen and Ghost Kitchens pilots received press but no disclosure of scaled rollouts or recurring revenue.

Substitution risk: Competing OEM robots cost far less; unsatisfied pilots can easily switch vendors.

Economic effect: High maintenance costs and low conversion rates undermine gross margins. With limited recurring revenue, Richtech relies on a constant influx of new trials to appear active.

Without verified uptime data, investors must assume field reliability remains below commercial standards.

4. Governance and Control

Richtech’s governance shows tight insider control and recurring related-party flows.

Concentration: Brothers Zhenwu (CEO) and Zhenqiang (CFO) Huang control roughly three-quarters of the voting power.

Insider transactions: Subsidiary buy-backs, inter-company loans, and “services” share grants favor insiders at minimal cost while preserving super-voting rights.

Board composition: Independent directors include veterans of China-linked issuers later accused of accounting misconduct, and members with little robotics experience.

Such control structures are common in promotional micro-caps, where internal cohesion substitutes for external oversight.

Implication: The governance design protects insiders through dual-class stock while public investors shoulder dilution risk.

A. Governance Red Flags

Zhenwu “Wayne” Huang (CEO)

Repurchased two company subsidiaries from Richtech for about $126k, despite the firm investing over $1 million into them.

Co-owner of Bison Systems LLC, which loaned money to Richtech and was later repaid.

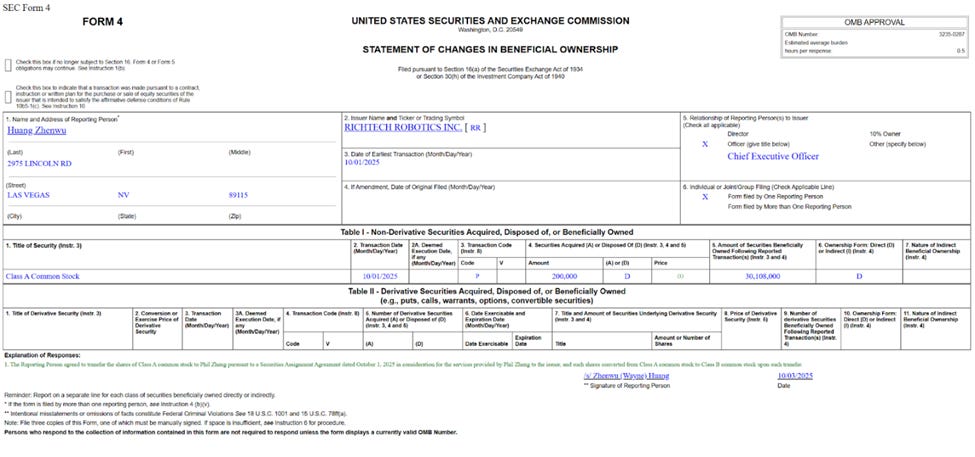

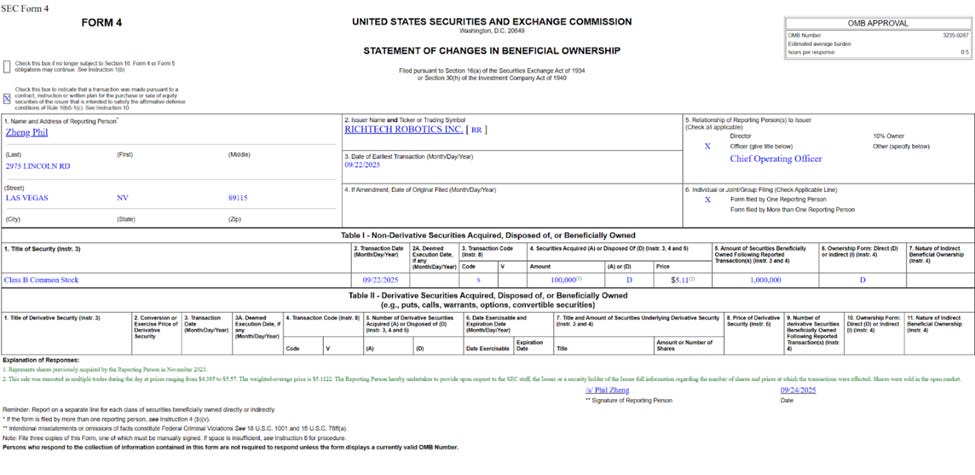

Personally transferred 1.2M Class A shares to the COO at roughly $0.02/share, later converted into high-vote Class B stock.

Linked through entities such as Uplus Academy and Huang Bros LLC, which appear in internal cash and control flows.

Zhenqiang “Michael” Huang (CFO; brother)

Joint owner of related-party entities involved in fund movements through Richtech.

Shares approximately 74% combined voting control with his brother.

Phil Zheng (COO)

Received 1.2M Class A shares for $30k, immediately converted to Class B, creating an effective acquisition cost near $0.02/share.

Extended insider loans to Richtech while serving as an executive, then sold shares during the early 2025 price spike.

On October 1, 2025, received 200,000 additional Class A shares from Huang “for services provided,” later converted to Class B—preserving insider control while diluting common shareholders.

Stephen Markscheid (Independent Director)

Board veteran of several U.S.-listed China-linked firms that later collapsed or settled fraud claims, including ChinaCast Education ($120 M CEO theft, settled class action), China Integrated Energy [CBEH] (fabricated revenue allegations, settlement), and JinkoSolar [JKS] (environmental-misrepresentation suit, settled).

Track record suggests passive oversight and recurring involvement with high-risk issuers.

John Shigley (Independent Director)

Former gaming executive with no evident robotics or automation background.

Reportedly associated with Henry Leong, a promoter connected to Richtech; while online claims mention a Nevada felony tax-fraud case, no verifiable public court record confirms it.

Raises questions about vetting rigor and board independence, especially given repeated affiliations with opaque or promotional figures.

Centralized Control

The Huang brothers jointly hold about 74% of total voting power, controlling multiple related entities that:

Loaned money to Richtech (Bison Systems LLC)

Reacquired subsidiaries at low prices (Uplus Academy)

Received preferential share transfers

This pattern supports concerns over:

Insiders enriching each other via “services” grants

Retention of power through voting-class engineering

A broader “optics over operations” approach, even within insider transactions.

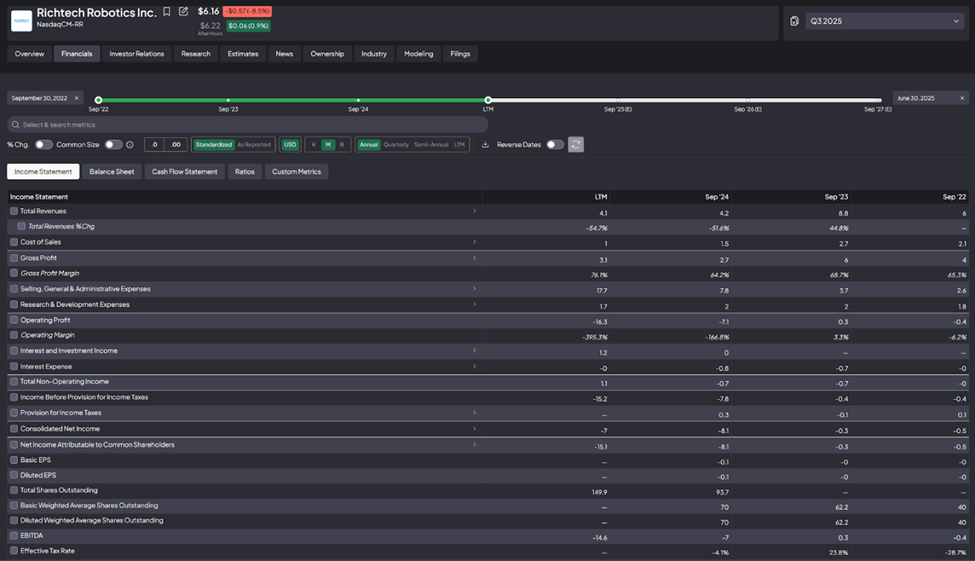

The uploaded snapshot illustrates a core contradiction: while insiders tightened their grip on voting control and issued themselves cheap equity, Richtech’s operational results worsened. Revenue remained flat, while operating losses expanded—underscoring a capital structure designed for control and promotion rather than performance. In this context, governance risk isn’t theoretical; it’s visible on the P&L

5. Promotion and Perception Engineering

While Richtech’s operational results have stagnated, its market valuation has often surged—driven less by performance and more by orchestrated visibility, speculative enthusiasm, and narrative control. The company’s public communications and promotional activity reveal a pattern of engineered perception, where awareness substitutes for execution.

Manufactured Visibility

RedChip listing: Richtech appeared on RedChip, a micro-cap investor-relations platform known for paid promotional exposure. While no direct Section 17(b) disclosure has surfaced, its inclusion there suggests deliberate engagement with publicity channels aimed at retail investors.

Stock-promotion phase: Following its November 2023 IPO, RR shares briefly soared to around $12, more than doubling before collapsing. Market observers attributed the spike to aggressive retail marketing and paid promotion campaigns that inflated early demand.

Staged partnerships: The company’s widely publicized “strategic partnership” with MAC USA, highlighted during its Nasdaq bell-ringing ceremony, unraveled when MAC

staff reportedly had no knowledge of any formal agreement—implying the event was designed primarily for optics rather than substance.

...implying the event was designed primarily for optics rather than substance. For further independent reporting on Richtech’s promotional practices and related-party activity, see the Capybara Research report (September 30 2025) [1].

Misleading Announcements

Walmart speculation: In August 2025, Richtech announced a Master Services Agreement with a “top global retailer”, sparking online speculation about Walmart involvement and fueling a sharp share-price rally. Evidence later indicated this referred only to a single pilot installation, not a corporate rollout.

Hype-as-a-Service: Henry Leong—a known Richtech promoter—later admitted the Walmart pilot was “just for promo” intended to drive investor interest. He described a strategy of placing robots in high-visibility venues such as MGM resorts or Home Depot stores to generate publicity and attract capital, regardless of commercial traction.

Retail Hype Engine

Social-media amplification: On forums like r/pennystocks and WallStreetBets, users circulated exaggerated claims of insider “buys” (often misinterpreted stock grants) and touted RR as a “100× AI play.” The “tiny float + AI” storyline became a meme-like catalyst for speculative trading bursts.

YouTube & blog coverage: Influencers and small-cap commentators released videos and articles—“Why You Should Buy Richtech Stock,” “Richtech Soars,” etc.—that, while sometimes including disclaimers, amplified the illusion of traction and legitimacy.

Viral feedback loop: Each promotional wave spawned reposts, short-term retail inflows, and renewed liquidity that conveniently aligned with Richtech’s financing windows.

Capital-Markets Alignment

Timed dilution: Share-price spikes consistently preceded or coincided with financing events. In early 2024, the company secured a $50 million Standby Equity Purchase Agreement, and by September 2025, it had filed to register up to $1 billion in new securities—each timed near retail-driven highs.

Analyst echoes: Small-cap outlets such as H.C. Wainwright issued bullish ratings around the same periods, echoing Richtech’s “Robots-as-a-Service” growth narrative and lending institutional veneer to the retail promotion cycle.

Visibility as liquidity: This pattern suggests that media presence functions as a capital-raising instrument, not merely investor communication. When sentiment peaks, the company monetizes attention through share issuance.

Conclusion

Richtech’s valuation appears to have been constructed through narrative engineering—a cycle where promotion creates trading volume, trading volume supports financing, and financing sustains further promotion. Its communications strategy mirrors a “hype-as-business-model” approach: claim partnerships,

amplify exposure, raise equity, repeat. Beneath the AI branding and patriotic imagery lies a firm whose true innovation lies not in robotics but in monetizing perception over performance.

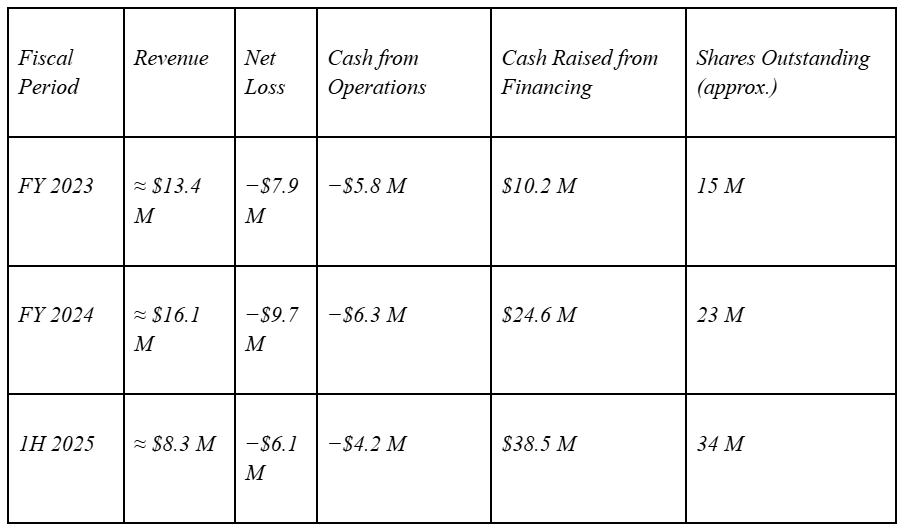

6. Financial Reality — Dilution as a Business

Richtech’s financial statements tell a single story repeated each quarter: cash from shareholders replaces cash from customers.

The company’s survival mechanism isn’t sales growth or margin expansion—it’s perpetual equity issuance.

In this sense, dilution isn’t a side effect; it’s the business model.

A. Revenue vs. Equity Proceeds

(Derived from 10-K 2024 and 10-Q June 2025)

Each year, financing inflows exceed revenue—sometimes by double.

Operating cash flow remains negative in every quarter, proving that Richtech’s “growth” is financed primarily through stock sales, not customers.

B. The Shelf Machine

Form S-3 ASR (Sept 2025): Registers up to $1 billion in mixed securities—equity, warrants, debt, and units—despite trailing-twelve-month revenue under $20 M.

Prior S-1 and S-8 filings: Enabled insider and employee resales following promotional run-ups.Standby Equity Purchase Agreement (SEPA): Executed Q1 2024 for $50 M with a micro-cap funder, allowing discounted share draws at management’s discretion.

Together, these vehicles create a permanent-financing loop:

hype → price spike → registration → issuance → cash burn → repeat.

...cash burn → repeat. Independent analysis from Capybara Research (September 30 2025) [link] details similar dilution mechanisms and alleged related-party flows. [1]

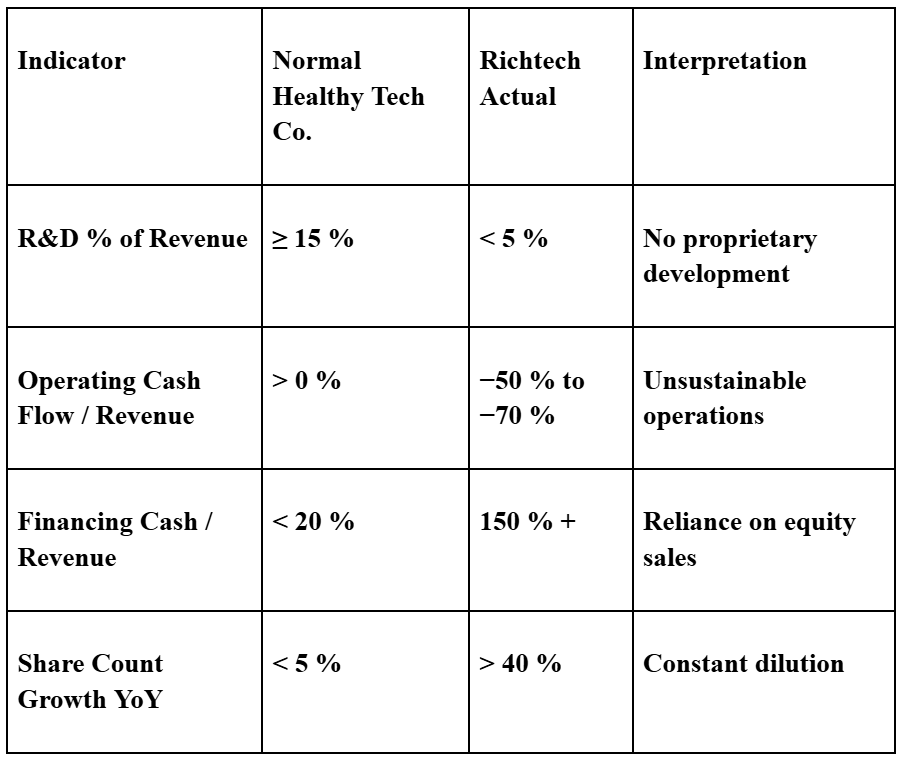

C. Cost Structure and Margin Compression

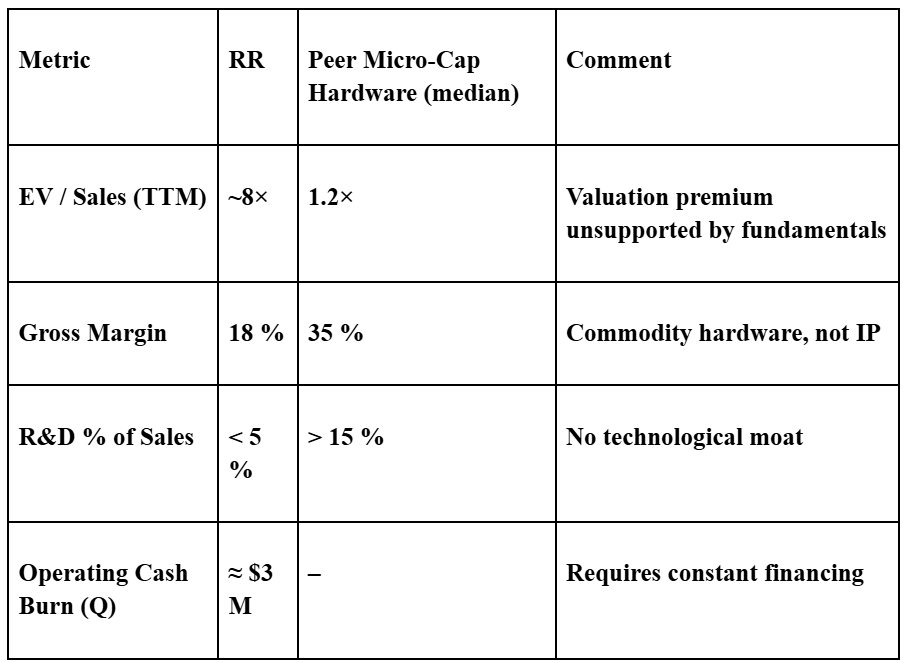

Gross margin: Fell from 31 % in 2023 to ~18 % by 1H 2025, as freight, warranty, and support costs doubled while volume stagnated.

SG&A: Continues rising, dominated by marketing and investor-relations outlays—categories that often overlap with external promotion channels.

R&D spend: Below 5 % of revenue, far beneath the 15–20 % common among genuine robotics developers.

The expense mix confirms that visibility, not innovation, consumes most resources.

D. Warrants and Convertible Overhang

Richtech’s SEC exhibits show multiple active instruments:

May 2025 Warrants: Five-year term, strike $9.60, with reset provisions; up to 5 million shares issuable after “reverse-split adjustment.”

Convertible Notes (2024): Convertible at 97 % of 10-day VWAP with 15 % daily sale cap—typical of “death-spiral” structures.

Employee Options (S-8): Roughly 2 million shares reserved.

Fully diluted exposure exceeds 50 % of the current float, ensuring a steady supply overhang even during rallies.

E. Cash Runway and Going-Concern Warning

At June 30 2025:

Cash: ≈ $6.8 M

Quarterly operating loss: ≈ $3.1 M

Financing capacity: Dependent on ongoing share issuance under S-3 and SEPA

Auditors included a going-concern warning, citing recurring losses and dependence on external capital.

Without new equity inflows, available cash covers less than two quarters of operations.

F. Economic Implication

Richtech’s income statement operates as a marketing document for its balance sheet.

Promotional activity maintains a tradable share price sufficient to extract more capital.

In substance:

Revenue is theater — dilution is the product.

G. Summary Indicators

Conclusion

Richtech’s financial mechanics complete the Illusion Loop: each promotional surge creates liquidity for the next equity issuance. Capital markets, not customers, fund the business.

Until the company demonstrates sustainable gross margins and positive operating cash flow independent of new stock sales, every rally merely resets the dilution cycle.

Financial Reality — Dilution as a Business Model

7. Final Synthesis and Risk Assessment

A. Narrative vs. Reality

The misalignment is systemic, not incidental.

B. The Playbook

Import → Rebrand → Resell

Announce → Amplify → Spike

Register → Issue → Replenish

Repeat

Each cycle monetizes attention while deferring proof of performance.

C. Regulatory and Listing Risk Possible exposure includes:

Section 17(b): Undisclosed paid promotion.

Reg S-K 404: Opaque related-party activity.

Rule 10b-5: Promotional statements lacking factual basis.

Nasdaq 5550(a)(2): Price compliance risk amid reverse-split cycles.

Given historic parallels among U.S.-listed China-affiliated micro-caps, regulatory review is plausible if financing momentum slows.

D. Valuation Disconnect

Investors are paying venture tech multiples for a low-margin reseller.

E. Risk Stack

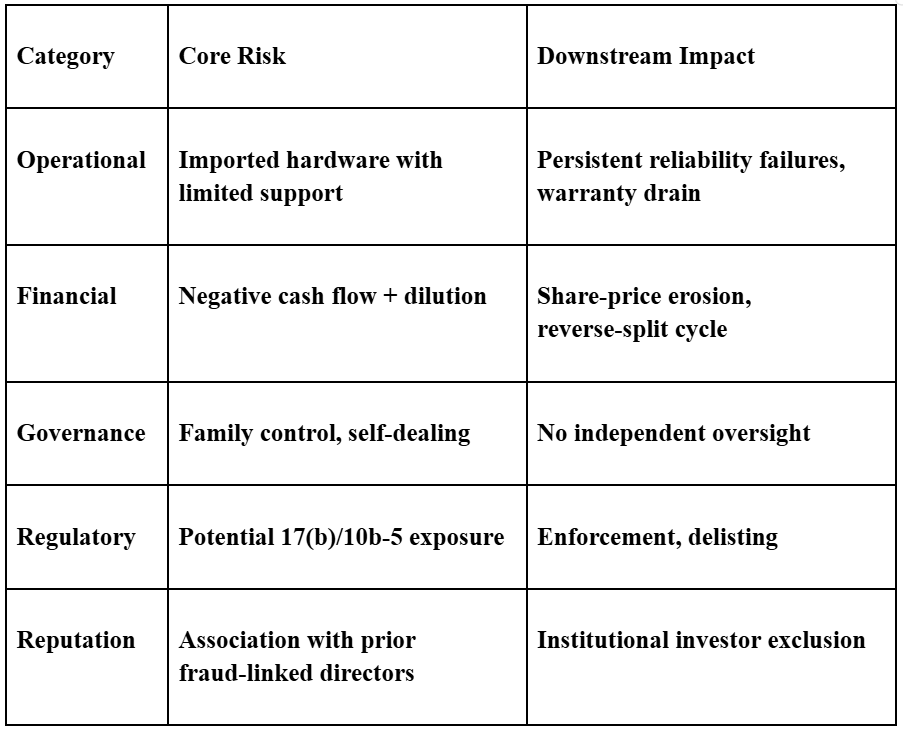

These risks reinforce each other, not offset them.

F. The Likely Trajectory

Absent verifiable IP, recurring contracts, and cash-flow turnaround:

Headline fatigue as “AI robotics” story saturates.

Trading volume declines once retail interest fades.

Capital-exhaustion and reverse-split..

Possible down-listing to OTC.

G. Investor Takeaway

Richtech Robotics epitomizes the modern micro-cap illusion—technology theater layered on financial engineering.

Its innovation lies not in robotics but in narrative control. Until the company demonstrates genuine intellectual property, recurring revenue, and operational transparency, investors should regard RR less as a tech firm and more as a marketing-financing loop that converts perception into capital.

Disclaimer & Disclosure

Fugazi Research is an investigative research publication focused on exposing accounting irregularities, mismanagement, and other red flags. Our reports reflect our opinions, which are based on public information and our own analysis. Fugazi Research, its affiliates, or related individuals may have positions, long or short in securities mentioned and may profit from price movements following publication. This is not investment advice. All investors should do their own research and consult with a licensed financial advisor.

[1] Additional reference: Capybara Research, “Richtech Robotics (NASDAQ: RR) – A China Hustle Wrapped in Patriotic Branding” (September 30 2025)

Exceptionally thorough forensic analysis of RR's business model. The hardware origin comparison with Sparkoz TN-series and OrionStar platforms is particularly damning - when identical systems are available direct from Chinese OEMs at 50-70% lower cost, the 'U.S. design IP' claim becomes untenable. What strikes me most is the pattern documentation: promotional timing aligned with financing windows, partnerships announced but never quantified in subsequent quarters, and gross margin compression from 31% to 18% despite 'scale.' The governance section connecting related-party flows (Bison Systems, Uplus Academy buybacks, Phil Zheng's $0.02/share conversion) reveals structural intent rather than oversight lapses. Your observation that SG&A spending dominates R&D by 3:1+ while revenue stagnates is a red flag few retail investors would catch. The shelf registration for $1 billion against sub-$20M trailing revenue is breathtaking - that's a 50x multiple on revenue for what's essentially an import-distribution chain. The going-concern warning combined with <2 quarters cash runway confirms the dilution treadmill. One question: have you identified any institutional holders who've maintaned positions through the volatility, or is the shareholder base purely retail rotation? The comparison table contrasting narrative vs. reality is devastating. Thanks for the meticulous documentation - this level of forensic work is rare in the microcap space.